Butte, America’s Story Episode 129 - Anaconda Smelter Stack

Welcome to Butte, America’s Story. I’m your host, Dick Gibson.

The Washoe Smelter stack in Anaconda is the tallest free-standing masonry structure in the world. Yes, it is. Historian Carrie Johnson laid to rest any technicalities and competition with the Washington Monument a few years ago.

What’s the stack made of?

There’s a 30-foot-high octagonal concrete base topped by 23,810 tons of bricks. They are special radial bricks invented by German brickmaker Alphons Custodis. Radial bricks are not rectangular, but have varying dimensions specifically intended for chimney and stack construction, and are larger than regular bricks. The 2,464,672 radial bricks in the smelter stack equate to more than 6.6 million common bricks. The Alphons Custodis company designed and built the stack using bricks made in Anaconda, but the exact source of clay is unknown. The company is still in business, as Hamon Custodis Inc.

The foundation was finished in May 1918, and the first brick was laid May 23, 1918, by smelter manager Frederick Laist. Even though he was with management, Laist was made an honorary life member of the Bricklayers and Masons Union for the event. The stack was completed in November, 1918, after 142 working days employing an average of 12 bricklayers per 8-hour shift (just one shift a day). 305,000 board-feet of lumber went into the scaffolding inside the growing chimney; that’s about 10,000 trees.

Brick mortar took 77 fifty-ton train cars of sand combined with 37 cars of fire clay, not counting the 50 cars of sand and 118 cars of crushed rock used for the 9,000-ton concrete base.

Resistance to wind pressure was a significant concern in the stack’s construction. The larger radial bricks make for fewer joints and greater strength, enough to resist a wind pressure of 33 pounds per square foot. There are also 24 steel bands within the brickwork to add to the stack’s resistance to horizontal stresses.

The top of the stack contained 20 lightning rods spaced around the 60-foot-diameter top. The one-inch points were tipped with platinum.

To celebrate the completion, an open-air platform was erected within the stack’s mouth. Elevators – one supposes they must have been more or less miners’ cages – took celebrants 585 feet above the ground. Ellen Crain’s grandmother fondly recalled the dancing she did there when she was 16 years old.

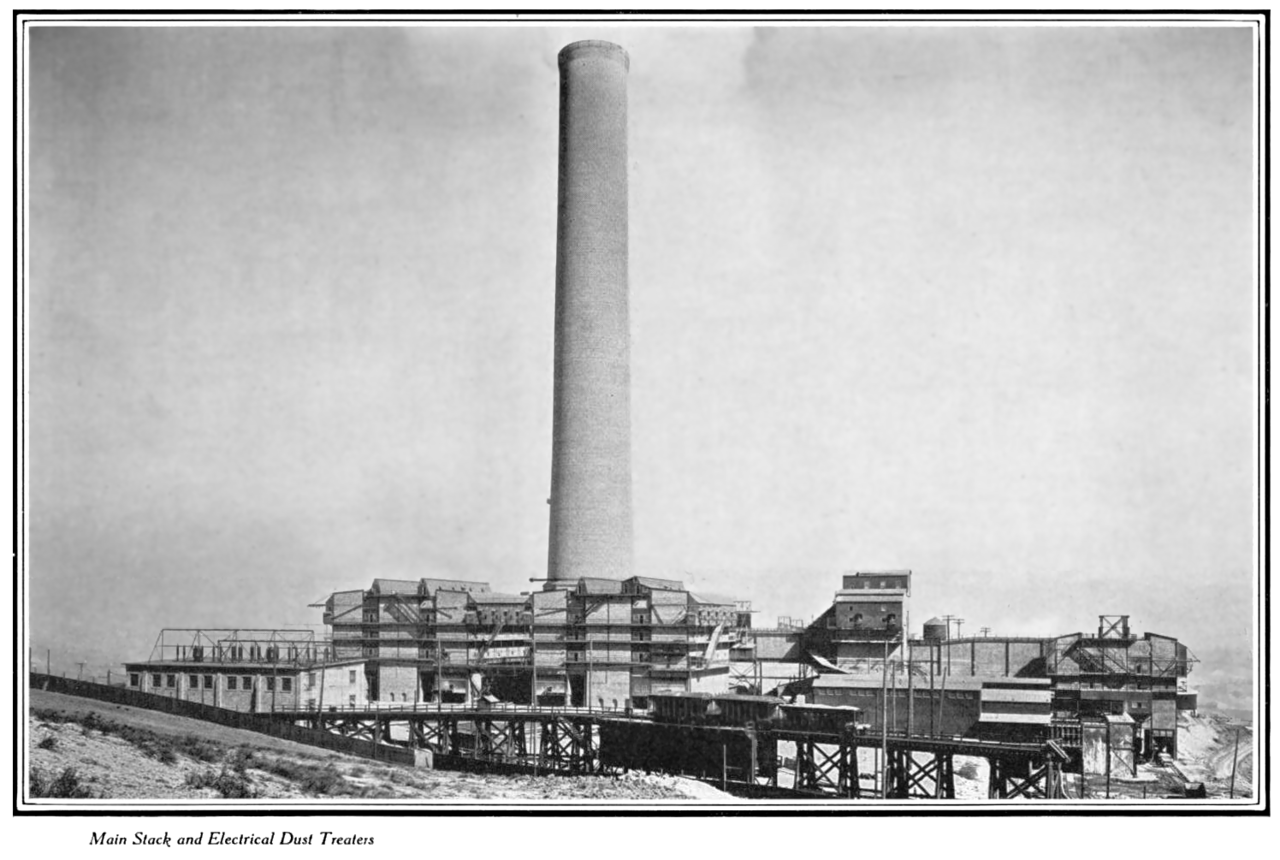

One of the goals of the new stack was to try to abate some of the arsenic and sulfur emissions that had come from the older 300-foot stack nearby, decimating the Deer Lodge Valley. They certainly tried – the stack contained 111 miles of chains, which were electrified so they would attract particulates traveling up the chimney with the gas, at a rated capacity of more than 3.5 million cubic feet of gas per minute. The first smoke came up the stack in late April and early May, 1919. 61 years later Anaconda-ARCO announced the closure of the smelter in September 1980, and today nothing but the stack remains.

As writer Edwin Dobb has said, "Like Concord, Gettysburg, and Wounded Knee, Butte is one of the places America came from." Join us next time for more of Butte, America’s Story.