Butte, America’s Story Episode 69 - Butte and The Nez Perce

Welcome to Butte, America’s Story. I’m your host, Dick Gibson.

In 1877, Butte had barely begun its rebound from the low point in 1874, when perhaps 60 or 100 people were still skulking around the old gold camp, scrabbling for leftover riches. With the first silver mines in 1875, Butte’s resurgence began.

In July 1877, western Montana was under a terror alert as Chief Joseph (also known as White Bird) and the Nez Perce went “on the warpath.” The Missoulian put out an extra on July 25, screaming “Help! Help! White Bird Defiant. Come Running,” dispatched by messenger to surrounding towns. The word reached Deer Lodge by June 28, where William A. Clark was visiting. He reportedly mounted a horse at 11:00 in the morning and rode the 42 miles to Butte in three hours.

The fire bell summoned residents to Loeber’s Hall & Brewery, at the southeast corner of Main and Broadway. The first military company was mustered almost immediately, with Clark elected captain of 53 privates and 10 officers, but in short order, three additional companies were formed, and Clark was promoted to major of the Butte battalion. A total of 153 men and 35 officers were ready to ride to the defense of Missoula – but there were nowhere near enough horses, or guns for that matter, for all of them.

Most of the miners were in fact not experienced horsemen, and many of the horses the battalion commandeered were unbroken, resulting in “laughable scenes” of horsemanship, but the rag-tag group eventually set out for Deer Lodge in buggies, hay wagons, and any other conveyance they could find. They made it as far as Garrison when word came from “the front” – Missoula – that the Nez Perce had left the Lolo area and headed south.

The Clark command returned to Deer Lodge and encamped at Warm Springs. There, Montana’s Adjutant General, James Mills, sent orders for the Butte men to proceed to the Big Hole, the expected destination of Chief Joseph. They had barely set out on July 30 when countermanding orders came from Territorial Governor Benjamin F. Potts. Potts recalled the sortie because the locals in the Bitterroot Valley were not cooperating with the military, for the simple reason that Chief Joseph had promised their safety if they allowed him to pass, and he paid for supplies with gold. Furthermore, the U.S. army was leisurely at best in the pursuit of the Nez Perce, so Potts advised Clark to abandon his unsupported attack. The governor was reportedly humiliated by the lack of federal support, and it wasn’t until October that Joseph surrendered in the Bear Paw Mountains.

The Butte contingent had one more role to play after being sent home July 30. General John Gibbon’s regular army forces attacked the Nez Perce encampment on the Big Hole on August 9-10. Thirty-one of his 206 men were killed and 38 were wounded, and he sent a plea to Butte for relief and ambulance support. Clark led 25 teams and 105 men to the scene to evacuate the wounded to Deer Lodge.

In an 1899 recap of the 1877 affair, the Butte Miner quoted Chief Joseph’s famous speech at the Bear Paw Battlefield, culminating with the line, “From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” And the newspaper article’s final line was “He has kept his word.” Chief Joseph died in 1904, and today’s historical view of the Nez Perce War is rather less condemning of Joseph’s clan than reports of 1877 would have it.

As writer Edwin Dobb has said, "Like Concord, Gettysburg, and Wounded Knee, Butte is one of the places America came from." Join us next time for more of Butte, America’s Story.

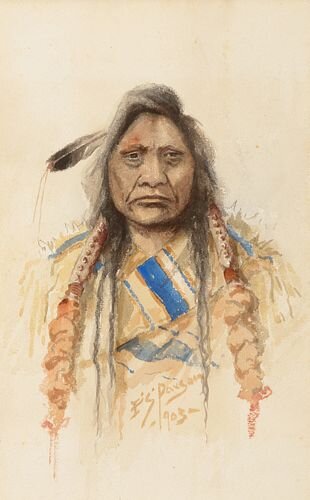

Chief Joseph